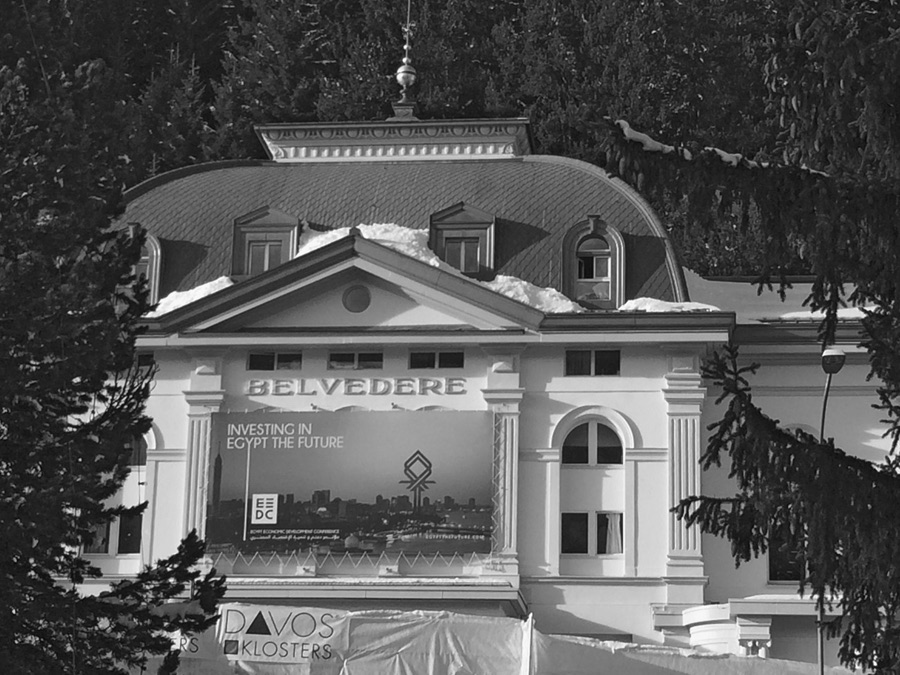

FOR ONE WEEK every year, the main street in Davos, the Promenade, turns into an unusual marketplace. As the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) commences in this upscale Swiss ski town each January, many of its posh hotels, cafes, and even museums turn into sites of an extraordinary kind of exchange. The colorful billboards displayed on the buildings have messages such as “India: Land of Limitless Opportunities,” “Make in India,” “Malaysia: Doing Business, Building Friendships,” “Brazil: A Country of Opportunity, Innovation, Sustainability, Creativity,” “Mexico: Seize the Day,” “Egypt: Invest in the Future,” and “Proudly South Africa: Imagine New Ways.” First-time visitors may find these advertisements puzzling. What kind of commodity is being showcased, and who might be the intended consumers? But for regular visitors, the spectacle of nations jostling for attention is a familiar sight during WEF week. These sites are the veritable front offices of “nation brands”: nations packaged and advertised as “attractive investment destinations” in global markets. During the past decade and a half, they have become popular landmarks on the global investment trail, well-known stopovers in the packed itinerary of investors forever in search of new profitable opportunities.

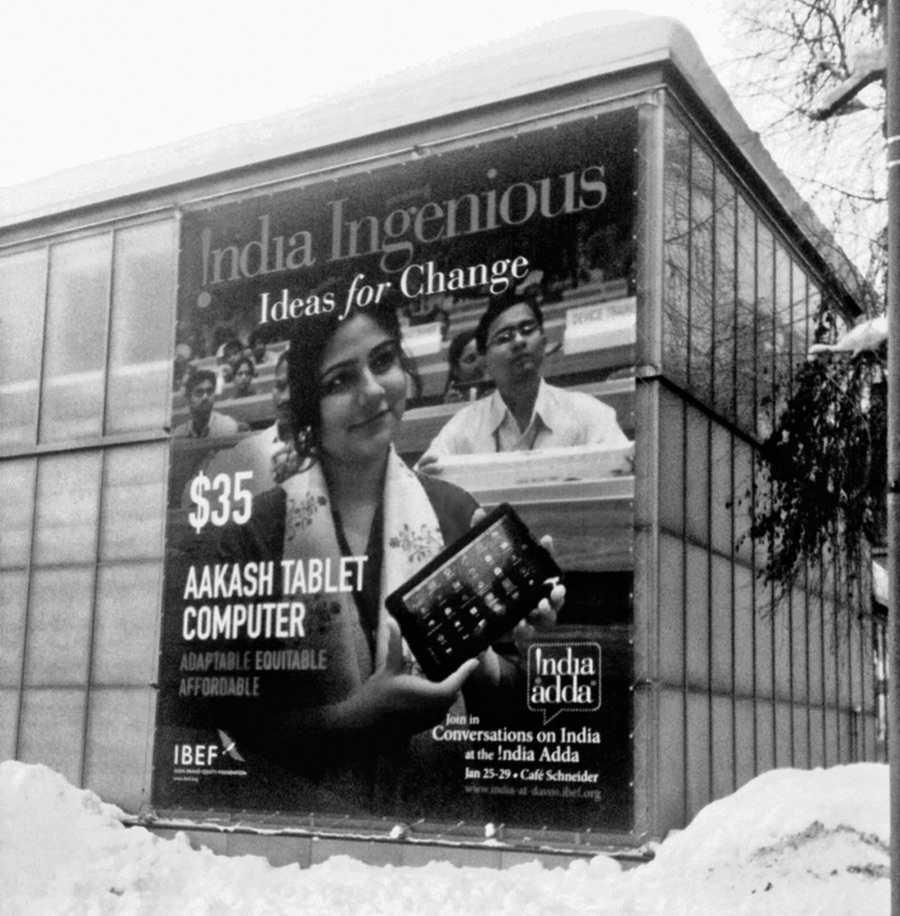

This exclusive world of nation brands is a strange, heady mix of optimism and anxiety, and it is seemingly forever on the move. On my first visit to Davos in 2012, I found myself seated next to two men dressed in smart business suits at Brand India’s lounge, India Adda—marketed as a “quintessential Indian hangout” representing India’s culture of commerce—at Café Schneider. I recalled seeing them the previous day on Brand South Africa’s premises in the Kirchner Museum, where an exhibition on the African growth story had been inaugurated. We exchanged our business cards, the first ritual of networking, and over cups of masala chai sponsored by the Tea Board of India, they expressed their love for India and all things Indian. They were both investment bankers at a major global investment-management firm specializing in emerging markets. As I glanced at their business cards, the one in the purple tie jovially explained his job as an explorer who discovers new investment hotspots in the world. “So where are those new hotspots?” I asked. He replied promptly, “In the emerging markets”: the bright rays of hope in Asia, Africa, and Latin America cutting through the dark clouds of recession in the Euro zone. “Mexico is coming up, Brazil is an attractive bet, and even Egypt is promising for those looking for alternatives,” his companion chimed in. “India is a long-term investment,” he said in a reassuring tone. But the emerging markets can be risky; “they heat up and cool down,” and therefore one had to be “ready to seize new opportunities,” the man in the purple tie added with a broad smile as they prepared to leave. In this futures market, it seemed, the investors were forever in search of new investment hotspots across the world, just as the nations hoped to be discovered and loved as attractive investment destinations. Due thanks and pleasantries done, they stepped out in the fresh snow that had covered the Promenade in the meantime. They were headed to the Mexico pavilion in Hotel Panorama, where a festive evening celebrating Mexico’s potential as an investment destination was about to begin.

FIGURE 1.1. India Adda publicity poster featuring technofriendly young Indians invites global conversations on India. Kirchner Museum, Promenade, Davos, 2012. Taken by author.

FIGURE 1.2. A street view of the India Adda/Make in India Lounge. Winter Garden, Café Schneider, Davos, 2015. Taken by author.

FIGURE 1.3. Hotel Belvedere featuring Brand Egypt. 2015. Taken by author.

This flash-in-the-pan encounter, polite and even charming, peppered with speculations and forecasts of risks and opportunities, is typical of how conversations unfolded in these settings. The affective language of hope and optimism—the compulsory good news the business world thrives on—that the two bankers had used to describe the futures market of nation brands was familiar to me. I had been drawn into this world at a particularly dramatic moment when India’s emergence and rise as a world player, propelled by its high economic growth performance and future potential, was being celebrated across the world. India was said to have “arrived on the global stage,” the primus motor of the Asian century that together with China was expected to eclipse Western hegemony in world affairs. It was as if the pace of history had accelerated in anticipation of a new time when India could finally be rescued from the “waiting room of history” and reoriented toward a limitless future.1 The early twenty-first century, we were told, was that of ascendance of the South, especially BRICS—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—the so-called big five. These countries were the leading stars of the many capitalist growth stories unfolding in the postcolonial and postcommunist nations. Envisioned afresh as an investment opportunity, the old third world was no longer a dark container of deprivation and overpopulation but a rich reservoir of resources and raw talent bolstered by its youthful demographic dividend waiting to be tapped by innovative entrepreneurs. The established hierarchies of north/south, rich/poor, core/periphery, developed/developing, and empire/colony seemed superfluous in the large-scale transformations redrawing the twentieth-century world map. The familiar world appeared to be upside down. In this unsettling capitalist geography, India’s emergence as a prominent nerve center of unbridled capitalism was a critical event in more ways than one.

FIGURE 1.4. “Malaysia: More Opportunities” at Hotel Panorama. 2015. Taken by author.

FIGURE 1.5. Brand Brazil bus in Davos. 2012. Taken by author.

FIGURE 1.6. Make in India campaign in Davos. 2015. Taken by author.

Recall here India’s established moral-political legacy as the prime mover of the third-world movement: the anticolonial coalition comprising newly liberated nations across Asia, Africa, and Latin America.2 Built on the shared experience of colonialism, the third world was more than a utopian dream of political liberation. Its cornerstone was economic independence seeking a fair redistribution of the world’s resources,3 the very opposite of the nineteenth-century free-trade imperialism that had created rich economic centers in the north and poor peripheries in the south. This move to fashion an independent third way beyond capitalism and communism in the mid-twentieth-century bipolar world underpinned India’s postcolonial nation-building efforts too. The sphere of economy itself was shaped as a “mixed economy”—an experimental hybrid of free-market enterprise and a planned economy—to realize the modernist dream of development.4 The Indian state was the key actor that planned large-scale development schemes and experimented in industrialization and import substitution in what came to be known as the tightly controlled License Raj, or a closed national economy. Against this background, India’s embrace of liberal economic reforms in the early 1990s was not merely an instance of liberal triumphalism sweeping the globe. It also signified an end of the third-world vision that India had helped shape in the heady years of independence. Given its sheer size and complexity, India’s shift toward capitalism was a momentous event in the organization of the world economy and the nature of global politics about to unfold. The official lounge of Brand India where I was seated was precisely a microcosm of these manifold shifts, a theater in which “New India”—the popular name for the postreform, technofriendly, high-consumption entrepreneurial nation—encountered the elite that governed the world. I was surrounded by cheerful images of the India growth story that foretold success and the unlimited potential of the nation to investors and policy makers. The publicity posters, glossy brochures, videos, and blogs were all geared to project India’s image in the language of desire: aspirations, promise, potential, talent, and limitless opportunities and growth. Dressed up as a branded commodity in Davos, the sign of India was called on to perform hope and promise for global capital, its nationalist dreams fully harnessed to the ever-enchanting project of capitalism.

The spectacle of the impending capitalist transformation of the nation-form has been in the public domain for a long time. An apt example of this hiding-in-plain-sight phenomenon is an Incredible India advertisement issued about a decade into the opening up of the Indian economy (fig. 1.7). The image features simple bold text reading “Open for Business!” against a rich crimson background. A common sign hung on shop fronts, “Open for Business” signals a commercial space accessible to potential consumers.5 Brought into the image frame of India, it is assigned a heavier task: to publicize the nation as a commercial enclosure, a space of limitless exchange and capital investment, now accessible in the global markets. That India is “open for business” is not just a witty turn of phrase; it is also an unambiguous description of the large-scale capitalist transformations—dubbed as the 1990s “new economic policy”—that deregulated the state control of the economy. Perhaps more significantly, the image is a disclosure of the making of the twenty-first-century nation-as-investment-destination phenomenon occurring in many parts of the world. The investment-destination model entails a full capitalization (transformation) of the nation into an income-generating asset: a new imaginary of the national territory as an infrastructure-ready enclosure for capital investment, its cultural identity distilled into a competitive global brand and its inhabitants—designated as demographic dividend—income-generating human capital that can be plowed back to generate more economic growth. In this logic, the injection of capital from outside is the vital force that fertilizes the earth of the investment-ready nation.6

1. Dipesh Chakrabarty, “Adda, Calcutta: Dwelling in Modernity,” Public Culture 11, no. 1 (1999): 118.

2. This radical vision of the world, by India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, eventually became the guiding principle of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) of nations, which desired to move beyond the bipolar hegemony of the United States and Soviet Union.

3. Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York: New Press, 2007), xvii.

4. This approach represented the middle path between free market and planned economy that would be used to create the modernist vision of an industrialized society. The mixed economy eventually came to be seen as a roadblock in India’s path to growing its economic muscle and becoming a great power.

5. The advertisement poster featured boldly in the 2007 International Tourism Bourse in Berlin, in which India was a partner country. The sign was hung at the main entrance to the convention. See also Dilip Bobb, “India Excel at International Tourism Bourse in Berlin, 2007,” India Today, March 26, 2007, https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/leisure/story/20070326-india-at-international-tourism-bourse-in-berlin2007–748967-2007-03-26#close-overlay.

6. The gendered nature of this transaction is apparent—the (masculine) outside capital fertilizes the (feminine) earth of the investment-ready nation.